Michelangelo: The Agony, The Ecstasy, and His Taste for Tortelli

A Renaissance shopping list reveals Michelangelo's daily diet and the human side of genius

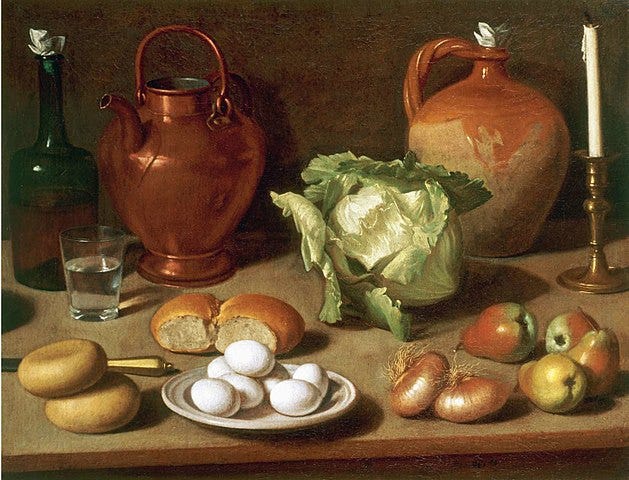

Among the treasures preserved at Casa Buonarroti in Florence is an unusual document that sheds light on the daily life of Michelangelo, the great Renaissance genius: a shopping list written in his own hand. Jotted down on the back of a letter and enriched with explanatory sketches—likely to assist his illiterate servant—this artifact reveals a surprisingly human side of the artist.

The date, March 18, 1518, places this document in the heart of the Lenten season, a time of particular liturgical significance for a devout Catholic like Michelangelo. This period, marked by fasting and abstinence, influenced his dietary habits, as reflected in this list.

Beyond revealing his dietary habits, this list provides insights into his private life and the culinary customs of his era.

What might seem like a modest grocery list to contemporary eyes, in the context of the 16th century, represents the food choices of a well-off artist. At 43 years old, Michelangelo already enjoyed a solid professional reputation and financial stability, allowing him to maintain a nutritious, high-quality diet.

This document intertwines with one of the artist’s most prestigious commissions: the façade of the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence, entrusted to him by Pope Leo X, son of Lorenzo il Magnifico. While Michelangelo was selecting marble for this ambitious project, he still found time to handle everyday matters, like drafting a humble shopping list.

Although the façade project was never completed—hindered by technical and financial difficulties that arose even during the material procurement phase—this shopping list still survives. It offers us an authentic snapshot of Michelangelo’s daily life, a man capable of blending his grand artistic visions with the practical necessities of everyday existence.

Here is the complete list:

Pani dua (two bread rolls)

Un bocal di vino (a jug of wine)

Una aringa (a herring)

Tortegli (tortelli)

Una salada (a salad)

Quatro pani (four bread rolls)

Un bochal di tondo (a jug of full-bodied wine)

Un quartuccio di bruscho (a quarter of dry wine)

Un piattello di spinaci (a dish of spinach)

Quatro alice (four anchovies)

Tortelli (tortelli)

Sei pani (six bread rolls)

Due minestre di finochio (two fennel soups)

Una aringa (a herring)

Un bochal di tondo (a jug of full-bodied wine)

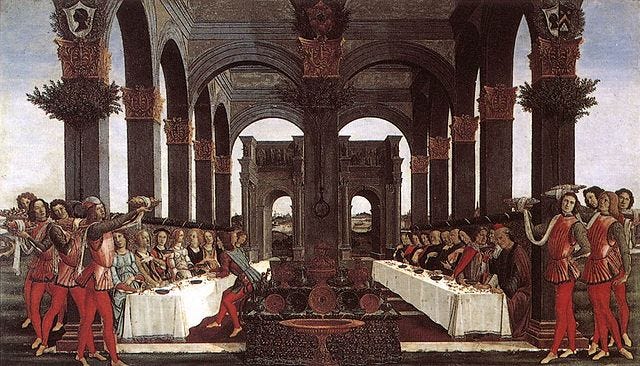

A Renaissance Table

The list, divided into three sections that likely correspond to different days, not only reflects a balanced and varied diet—suitable for Lent and consistent with the master’s frugal habits—but also a practical approach to planning.

Known for his attention to detail, Michelangelo selected foods with an eye for preservation—such as salted or dried herring—and freshness, such as spinach. This careful selection was essential to guaranteeing regular, adequate meals in an era without modern refrigeration.

This document also highlights aspects of Renaissance cuisine, which blended regional flavors and external influences. The tortelli, a type of stuffed pasta, and fennel soup, a dish typical of the Apuan region, point to the culinary traditions of the area where Michelangelo likely resided during this period.

The anchovies, likely fished in the waters of Versilia, represent a fresh local product, while herring, known as the “fish of the city,” arrived dried, salted, or smoked from northern Europe. Bartolomeo Scappi, in his treatise on Renaissance cuisine, notes that these “are brought from Flanders and France through the Rhine River to Italy, preserved in brine in barrels.”

One notable element in this list—which challenged my belief based on previous readings—is the constant presence of wine at Michelangelo’s table. While maintaining otherwise modest habits, the master was not a teetotaler and included this key element of the period’s diet in every meal.

This list combines simplicity and sophistication, making it an ideal starting point for exploring the foods and culinary habits of the Renaissance.

In my next article, I will focus on some items on Michelangelo's list and discuss the techniques and influences that made them integral to 16th-century diets.

Stay with me as I take a closer look at the Renaissance table!

You may also enjoy some suggestions for further exploration:

Michelangelo's Grocery List, And The Reason He Sketched It

Also, if you’re fascinated by Renaissance culture, you may be interested in my articles exploring Monsignor della Casa’s Galateo, a cornerstone of etiquette and refined manners in the 16th century, and Isabella d’Este’s legacy.

I didn't get the notification for this article, I'm glad I found it! Michelangelo had an excellent diet, good for the Maestro.

I'm curious about the fennel soup. Could you buy soup readymade? Did it come in a jug? Or maybe he just means the ingredients to make it.