Isabella's True Colors

A Renaissance Portrait's Journey From A Soft Mocha Mousse Hue To A Vibrant Mystery

Pantone has announced Mocha Mousse as the color of 2025—a warm and muted tone that evokes earthy shades and the depth of coffee.

The Mocha Mousse shade evokes the tones found in some of Leonardo da Vinci's drawings, particularly the “Portrait of Isabella d'Este”, where similar tones emerge in its careful use of charcoal, sanguine, and yellow pastel.

The portrait, dated around 1500, is a preparatory study for an oil painting that Leonardo never completed (or so it was thought). It is now preserved at the Louvre Museum in Paris.

Leonardo created this work during a brief stay in Mantua in late 1499, following his departure from Milan, which the French conquest under Louis XII had destabilized. In Mantua, he met Isabella d'Este, the influential marchioness renowned for her patronage of the arts and her wide-ranging cultural interests, who commissioned him to create her portrait.

Isabella d'Este was a key figure of the Italian Renaissance, not only for her political influence but also for her intellectual and artistic connections. Leonardo's portrait of her is understated yet conveys her standing and personality.

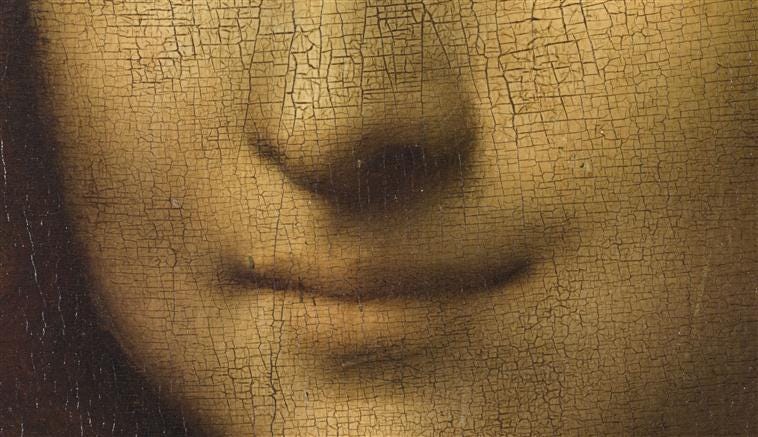

This drawing has also been cited as a possible precursor to Leonardo's Mona Lisa (1502–1506). The similarities between the Portrait of Isabella d'Este and the Mona Lisa are evident, particularly in the positioning of the hands.

Isabella D'Este: The Tenth Muse of Mantua

Isabella d'Este (1474–1539), Marchioness of Mantua, was one of the most influential figures of the Italian Renaissance. Renowned for her discerning patronage of the arts, Isabella embodied the era's ideals, combining cultural sophistication with strategic governance. Born into the Este family in Ferrara, she was educated in Latin, Greek, music, dance, and philosophy.

As Marchioness, Isabella cultivated one of Italy's most refined courts. She materialized her artistic interests in two physical spaces: the studiolo and the grotta. These were private spaces, authentic "rooms for her own," that symbolized her autonomy in cultural and intellectual matters.

The studiolo featured commissioned works by Andrea Mantegna, such as "Parnassus" and "The Triumph of the Virtues," which blended classical mythology with Renaissance ideals. Following Mantegna's death in 1506, she expanded her collection with mythological works by Perugino, Titian, and Correggio.

Adjacent to the studiolo, the grotta housed an array of antiquities, including coins, gems, and medals, acquired with the advice of experts.

Her pursuit of artistic excellence is notably exemplified in her interactions with Leonardo da Vinci regarding the commission of her portrait. This episode reveals both Leonardo's notorious reluctance to complete commissions and Isabella's persistence. Indeed, she maintained contact with him over several years, attempting to acquire works, demonstrating her determination and understanding of the importance of having works by the most celebrated artists of her time.

Isabella was a demanding and meticulous patron, offering her artists precise instructions to ensure her vision was realized. A famous example is her commission to Giovanni Bellini, who ultimately declined also due to her stringent requirements. This episode illustrates the delicate balance between patron expectations and artistic autonomy, a dynamic central to Renaissance art.

Her influence extended far beyond the visual arts. Isabella actively participated in intellectual circles, corresponding with humanists like Pietro Bembo. She was also immortalized in Ludovico Ariosto's “Orlando Furioso”, which celebrated her wisdom and influence.

From your noble lineage will arise she,

a friend of great deeds and noble studies,

whom I cannot decide whether to call

more graceful and fair, or wiser and more chaste,

generous and magnanimous Isabella.

With her radiant light, both day and night,

she will illuminate the land by the Menzo,

to which Ocno's mother gave its name.

Additionally, her court became a hub of musical innovation, hosting composers such as Bartolomeo Tromboncino and Marchetto Cara, who developed the frottola, a precursor to the madrigal.

Politically, Isabella played a significant role in Mantua's governance. During her husband Francesco Gonzaga's military campaigns, she effectively managed the state, balancing diplomacy and administration. Following Francesco's death in 1519, Isabella served as regent for her son Federico II until 1521, navigating Mantua through a critical period of political uncertainty.

Isabella's approach to collecting and displaying art established enduring models for future generations. Her systematic collecting practices, where works were chosen not merely for their individual merit but for their contribution to a broader artistic and intellectual program, significantly advanced art patronage.

The studiolo and grotta became influential prototypes for later collectors, inspiring the development of the cabinet of curiosities (Wunderkammer) in subsequent centuries.

Moreover, her innovative practice of displaying ancient and contemporary works in dialogue with each other and her active role in shaping artistic creation through detailed iconographic programs established new standards that influenced collecting practices well beyond the Renaissance period.

The works and artifacts she collected, along with her extensive correspondence, which includes thousands of letters that are available today, offer a unique perspective on her life. They reveal how she used cultural patronage and political strategy to assert her independence and influence.

The Strange Case of the Portrait in Lugano

The story of Isabella’s portrait begins with a preparatory sketch Leonardo da Vinci created in 1499/1500 during his stay in Mantua. Later, he took the sketch with him to France. Despite Isabella's persistent requests, Leonardo never completed the commissioned portrait or returned the preparatory sketch to her.

For over 500 years, this seemed to be the episode's conclusion.

However, in 2013, an unexpected twist occurred: a supposed 'colored' portrait of Isabella d'Este, allegedly based on Leonardo's preparatory sketch, surfaced in a private vault in Switzerland.

The painting's attribution to Leonardo da Vinci remains unresolved. The legal proceedings that followed its discovery reveal a complex intersection of art history, law, and international cultural heritage protection.

The following account attempts to piece together the story, drawing on newspaper articles published between 2013 and 2019.

In 2013, Italian authorities began investigating a painting discovered in a Swiss vault in Lugano. The work, a 61x45.5 cm oil on canvas depicting Isabella d'Este, was attributed to Leonardo da Vinci. A lawyer representing an Italian family was offering the painting for sale at €95 million.

The discovery initiated parallel proceedings: legal investigations and scholarly debates about its authenticity.

The painting's existence became public in October 2013. Several experts, including Leonardo scholar Carlo Pedretti, supported its attribution to Leonardo, citing radiocarbon dating results and stylistic analysis.

However, other scholars expressed significant doubts, noting that the Louvre's catalog explicitly states Leonardo never executed the painting. Critics also highlighted stylistic inconsistencies and the absence of historical documentation linking Leonardo to a finished portrait.

The legal proceedings intensified in 2014 when a new attempt to sell the painting emerged, this time for €120 million. Italian authorities filed a second request for international legal assistance, leading to a Swiss police raid on a trust company vault in Lugano in February 2015. The Italian prosecutors' investigation suggested connections to an international art trafficking network.

The debate over authenticity continued to develop. Supporters of Leonardo's attribution cited the quality of execution and compositional elements, while skeptics noted the absence of his characteristic sfumato technique and departures from his documented working methods.

The legal case progressed through several stages. In 2017, an Italian court found the painting's owner guilty of illegal exportation, imposing a 14-month prison sentence.

The owner contested this verdict, claiming family ownership spanning generations and the painting's presence in Switzerland predating current exportation laws by over a century. The Federal Criminal Court of Switzerland supported the owner's appeal against repatriation to Italy while maintaining the artwork's sequestration pending Italian court decisions.

In 2018, the Swiss Federal Criminal Court ordered the painting's return to Italy, citing its significance as cultural heritage.

This ruling was overturned in 2019 by the Swiss Supreme Court, which determined that Swiss law prohibits the illegal exportation of cultural assets only when the item appears in an official Italian inventory of protected cultural goods. The "Portrait of Isabella d'Este" had no such listing. Consequently, the court ordered the painting's release from sequestration and its return to the owner, concluding the legal proceedings.

Today, the painting remains in Switzerland, and its legal status is resolved, but its artistic identity is still contested. The question remains whether this work represents a lost Leonardo masterpiece, a contemporary follower's interpretation, or a later creation.

Mona Lisa's Smile

From 2025's Mocha Mousse, we have traveled through a story spanning more than five centuries, connecting Leonardo's genius, the ambition of one of the Renaissance's most significant patrons, and a modern-day international art mystery.

It is emblematic of how a single portrait can tell us so much about the relationship between artists and patrons, the complexities of the art market, and the challenges of protecting cultural heritage.

Above all, it demonstrates how every work of art carries with it not only its history but also its mysteries.

Perhaps it's no coincidence that Leonardo, who began with Isabella's portrait and went on to create the Mona Lisa, gifted the world two enigmatic smiles - timeless riddles from the Renaissance that still defy explanation.

Suggestions for Further Reading:

Renaissance woman: Isabella d’Este

If you are into historical fiction, you may appreciate: Maria Bellonci, Private Renaissance (1985)

Also, if you are interested in the Italian Renaissance, you may enjoy my previous posts:

The monetary value difference between the name and the no name of a work of art never ceases to amaze me. The painting hasn't changed, just the provenance. And history sleuthing through the mists ( mystery) of time.... thankyou for a fascinating read.

A story as mysterious as Mona Lisa's smile. I'm so jealous of Isabella's studiolo and grotta.