In May 1914, while Europe is still formally at peace, the artist Giacomo Balla signs a manifesto titled Le vêtement masculin futuriste.

The manifesto - one of the tools of cultural and political intervention favored by the Futurists - is written in French and proposes a radical reform of dress: bright colors, asymmetries, dynamic lines, and functional simplicity.

The Futurist suit is the uniform of a new humanity in motion, driven by speed and decisive action.

The outbreak of the Great War

At the end of June 1914, in Sarajevo, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand sets off a chain reaction that, within a few weeks, drags Europe into war - the “war, the world’s only hygiene” invoked by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in his Manifesto of Futurism (1909).

Italy, bound by the Triple Alliance yet uncertain about what to do, initially chooses neutrality.

It is in this climate of uncertainty and tension that the manifesto changes its nature.

A Program Against Neutrality

On 11 September 1914 a new, expanded version of the manifesto appears. It is written in Italian, bearing a new and unmistakable title: Il vestito antineutrale. Manifesto futurista (The Anti-Neutral Suit. Futurist Manifesto).

It is more of a political rewriting than a simple translation of the French text; to get around censorship, its propaganda content was camouflaged behind the seemingly harmless topics of garments and colors.

The shift from the Futurist suit to the anti-neutral suit marks a qualitative leap: fashion becomes a tool of interventionism.

The declared target is the neutrality of the colors then in fashion, but the sartorial attack conceals a broader aim: Italy’s political neutrality.

Not by chance, the manifesto opens with two epigraphs that immediately set the tone. On the one hand, the famous line from the first Manifesto of Futurism of 1909:

We glorify war, the world’s only hygiene.

On the other, a reference less immediate yet rich in meaning:

Long live Asinari di Bernezzo!

the Risorgimento hero celebrated by Marinetti as early as 1910 for his irredentism.

The message is clear: war is seen as the completion of the Risorgimento, the settling of accounts with the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which still controls Trento and Trieste.

In the Anti-Neutral Suit this vision takes the form of a political program. The manifesto lists what “today we want to abolish”: neutral colors; pedantic, “Teutonic” shapes; striped and checked patterns; mourning clothes; symmetry; starched collars and cuffs; useless buttons.

It is a list that strikes at the heart of bourgeois taste, linking it to immobility, cowardice and death. Heroic deaths, it declares, should not be dressed in black, but remembered in red.

One thinks and acts as one dresses. Since neutrality is the synthesis of all forms of past-worship, we Futurists today brandish these anti-neutral suits, that is, joyfully warlike ones.

By contrast, the manifesto defines the qualities of Futurist clothing: it must be

aggressive, able to multiply the courage of the strong and unsettle the weak;

agile, to support the surge of running and charging;

dynamic, with geometric patterns that inspire a love of danger and a hatred of immobility;

simple and comfortable, suited to aiming a rifle or plunging into water;

hygienic, so the skin can breathe during marches;

joyful;

illuminating, made of phosphorescent fabrics, capable of igniting boldness, casting light when it rains, and correcting the greyness of dusk;

volitional, imperious like commands issued on the battlefield;

asymmetrical;

short-lived, to renew pleasure constantly;

variable, through “modifiers” (pneumatic buttons) that allow the garment’s shape to be changed at will.

The suit must be an amplifier of energy, almost a moral prosthesis.

Futurist shoes, of course, will be “fit to cheerfully kick all neutralists.”

And Futurist colors are vivid, “muscular”… As listed by the manifesto, they read like a Futurist poem in their own right:

violettissimi, rossissimi, turchinissimi, verdissimi, gialloni, aranciooooni, vermiglioni.

(purplest, reddest, turquoisest, greenest, big yellows, big oraaanges, vermilions.)

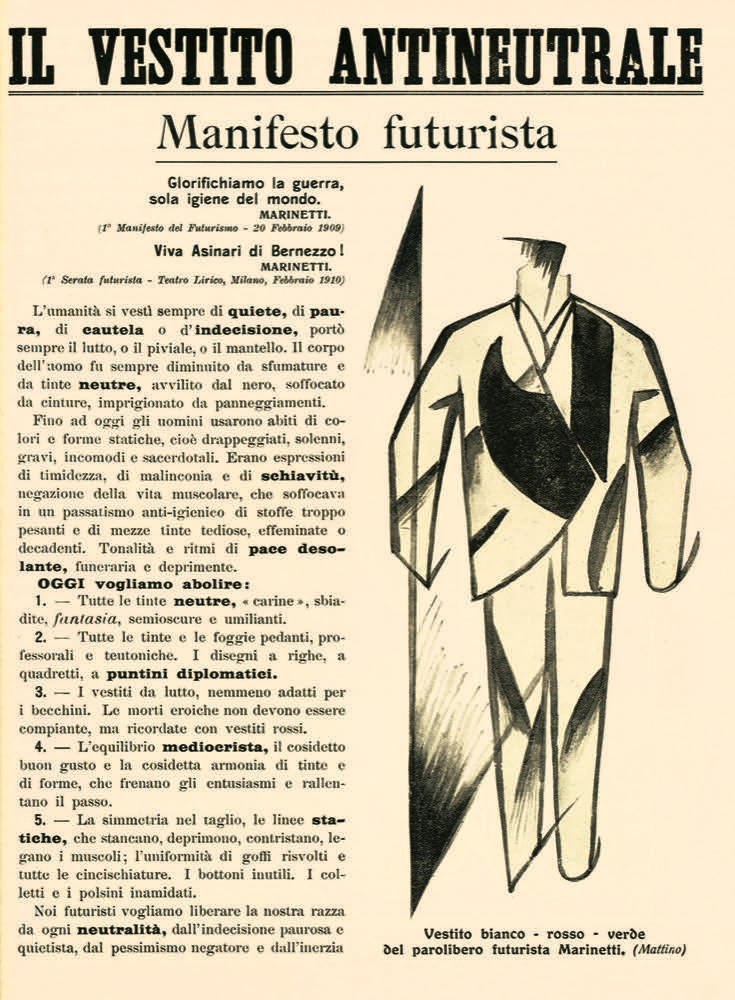

The manifesto is enriched by several models designed by artists of the group.

These include the white-red-green day suit (the Italian tricolor) by the “Futurist free-word poet Marinetti,” the red one-piece suit (the forerunner of the jumpsuit) by the Futurist painter Carrà, and the green sweater with red and white jacket by the “Futurist noise-artist Russolo, volunteer cyclist.”

From Page to Street

In December 1914 a third version of the manifesto appears, a reprint of the official version but with a different image on the front page: the tricolor suit worn by the “Futurist free-word poet Cangiullo” during demonstrations against the neutralist professors of the University of Rome.

The caption specifies the context: the protests of 11–12 December 1914.

By now, the manifesto has become a militant document, tied to concrete events and real clashes. Within a few months, the Futurist suit has turned into the anti-neutral suit.

What has changed is not only the language, from French to Italian, but the very function of the project. Here, fashion does not serve to mark an aesthetic avant-garde, but to declare a political position.

The following year, on 24 May 1915, the Futurists finally get what they want: Italy enters the war against the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It is no surprise that many of them volunteer for the front, often paying with their lives for the consistency between ideas and actions.

In 1914, before the war is fought, Futurism puts it on. The dressed body becomes the first battlefield.

I have this hanging on my wall! The middle illustration, in Italian. I found it years ago in a bookstore in NYC and framed it. I never knew what it was, just have enjoyed the design and typography. I'm so happy to see this.

Cool read, I’ve always been fascinated by the futurists