I have always been fascinated by the historical period nostalgically called the Belle Époque: an expression coined in the aftermath of the horrors of the First World War to look back at an era when humanity still indulged in the illusion of unstoppable progress and endless prosperity. In the Belle Époque lie the roots of our present: from scientific and technological discoveries (notably electricity and vaccines) to industrialization, mass culture, and the first steps toward women's emancipation, to name just a few of the most significant aspects.

It is easy to be captivated by the luxury and opulence that often emanate from images of that golden age. Still, it is equally intriguing to delve into the simmering mix of contradictions and dark undercurrents lurking beneath the surface, ready to erupt violently in the cataclysm of the First World War.

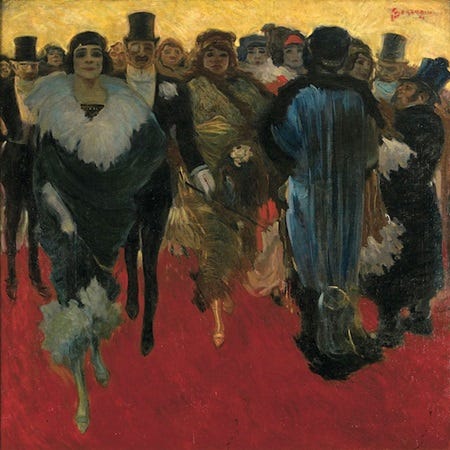

Recently, I came across an artwork, Mondanità or Uscita dal veglione by Aroldo Bonzagni (1910), which perfectly captures the carefree side of the Belle Époque. The subjects of Milan’s high society are depicted as they leave a party and strut confidently down a red carpet, brimming with euphoria and trust in a bright future. Yet, knowing Bonzagni, it is impossible not to detect a subtle note of sarcasm: an implicit critique that reveals how fleeting this ostentatious luxury is, and how oblivious this bourgeois class is in its arrogance, standing on the brink of decay.

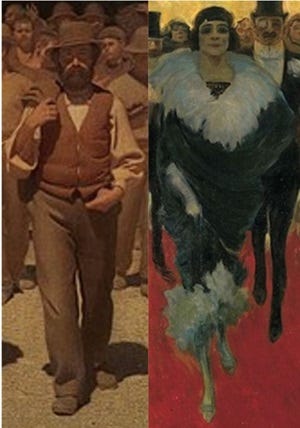

This work immediately made me think, by contrast, about another iconic image from that time: Il Quarto Stato (The Fourth Estate) by Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo (1901). In it, we see another march—a solemn procession of the working class, a compact group of men and women advancing with a determined step towards a future of social redemption.

Indeed, during the Belle Époque, workers' struggles marked a decisive moment in European social history. Trade unions and socialist parties emerged, born in response to the brutality of the industrial system, aiming to secure better living and working conditions for the proletarian masses. Strikes and protests spread rapidly, and despite often violent repression by the authorities, they led to the approval of the first labor laws and the creation of organizations to defend workers' rights.

Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo conceived Il Quarto Stato as a symbolic and artistic response to these repressions, particularly inspired by the so-called 'Bava Beccaris massacre' of 1898, when, in Milan, during protests ignited by rising bread prices and extreme poverty, General Bava Beccaris ordered troops to fire on the crowd, causing numerous civilian casualties.

In an almost symmetrical pose, the protagonist of Pellizza da Volpedo's work and the female figure in Bonzagni's painting, separated by a decade, embody the two opposing sides of the Belle Époque: on one side, the solidity and pride of the worker advancing firmly towards a future of vindication; on the other, the frivolity and elegance of an elite that proceeds confidently, immersed in luxury and seemingly unaware of the profound changes stirring within society.

Just a few more years, and images would tell of yet another march—just as resolute, but with a far darker fate: that of soldiers departing for the front, stepping forward with the same determined pace, yet heading towards the unimaginable horror of World War I.

Looks somewhat frightening up to date or Kim?

The comparison you make between those figures is very clever. They both stride ahead, but a what a stark contrast in theme!