Michelangelo’s Half-Full Glass (of Wine)

Three dishes from the Master’s shopping list unveil the flavors and traditions of 16th-century Italian cuisine.

Were Michelangelo's tortelli anything like the ones sold in today's delicatessens?

Does the constant presence of wine on his table reveal a man of indulgence or simply mirror the customs of Renaissance dining?

And what flavors lingered in that fennel soup, steeped in the spices of his time?

These three seemingly mundane notations on his shopping list became doorways into a broader world. Each dish carries a story beyond its ingredients.

Tortelli speak of ingenuity in the kitchen, where cooks transformed whatever was in the pantry into artful pasta. Wine flowed through daily life as both necessity and pleasure, its presence shaped by practical needs and divine ritual. Fennel soup, despite its simplicity, preserved the medieval passion for bold spices while embracing Renaissance refinement.

Through these three elements of Michelangelo's market notes, we discover how one of history's greatest artists shared in the daily rhythms of Renaissance dining.

Missed the first episode of this article?

Tortelli

In Michelangelo's shopping list, tortelli are mentioned twice, emphasizing their popularity in Renaissance cuisine and their appeal to Michelangelo.

The term tortello, a diminutive of torta, referred to a sheet of pasta filled with various ingredients—meat, fish, vegetables, or sweet fillings. This versatility contributed to their widespread presence since the Middle Ages, making them a common and adaptable dish suited to various tastes and occasions.

The Tuscan fondness for tortelli is also recalled in "Morgante," an epic burlesque poem by Florentine poet Luigi Pulci published in 1478. In this work, which blends heroic and humorous episodes, the character Margutte praises earthly pleasures, including food and drink, with these lines:

Ma sopra tutto nel buon vino ho fede,

E credo che sia salvo chi gli crede.

E credo nella torta e nel tortello,

L’uno è la madre, e l’altro è il suo figliuolo.But above all, in good wine I believe,

And I trust that those who believe in it are saved.

And I believe in the cake and in the tortello,

The first is the mother, and the second is her child.

With these verses, Pulci celebrates tortelli as food and elevates them to a symbol of the simple, earthly pleasures that shaped daily life in the Renaissance.

The poem's irony highlights the contrast between these tangible joys and the lofty ideals celebrated in the epic poetry of the time, reaffirming the importance of food in everyday existence.

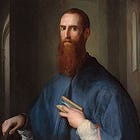

Bronzino, Portrait of the Dwarf Morgante - front (1552) housed at Palazzo Pitti (Florence). The subject, Braccio di Bartolo, a well-known court jester at the Medici court, was nicknamed "Morgante" after the giant in Luigi Pulci's Morgante—a humorous contrast to his physical stature.

Fennel Soup

Given his connections with Rome's elite circles, including the papal court, Michelangelo was likely familiar with recipes like those described in Bartolomeo Scappi's monumental cookbook.

Scappi, the personal cook to Pope Pius V (1566–1572), published his treatise in 1570, just a few years after Michelangelo's death. His work provides a detailed portrait of Renaissance cooking, with over a thousand recipes reflecting the culinary sophistication of the era, from everyday meals to elaborate feasts.

Scappi's work is more than just a cookbook—it is a detailed manual on food preparation, covering everything from the treatment of meats and fish to desserts and vegetable dishes. One section even addresses cucina di magro, meals designed for religious fasting periods like Lent. The treatise also provides insights into the tools and layout of Renaissance kitchens, illustrating the complexity of culinary practices during this time.

Among the many recipes Scappi recorded, the minestra di finocchi selvatici (wild fennel soup) is a good example of the simplicity and refinement of Renaissance cuisine. Its preparation reflects the Renaissance balance between resourcefulness and a preference for intense, aromatic flavors inherited from the Middle Ages.

Here is the recipe as Scappi recorded it. With some imagination, one can envision Michelangelo enjoying a similar dish during the early 1500s.

Piglisi il finocchio nella sua stagione (…) dico quei germugli bianchi che nascono ne i piedi delli finocchi seluaggi, leuisi la prima scorza, et piglisi la parte piu tenera, lauinosi, et faccianosene mazzuoli come delli broccoli, et ponganosi in un uaso nel qual sia oglio, acqua, et sale, et faccianosi cuocere bene, et per far spesso il bordo pongauisi una mollica di pane che sia stata in molle nel brodo, et passata per lo foratoro, aggiungendoui pepe, et cannella, et zafferano, et come saranno cotti, seruanosi caldi con il lor brodo sopra. Et non essendo vigilia ponganosi a cuocere con essi croste di cascio Parmeggiano, et in loco dell’oglio, ponganuisi butiro. Si può anche far minestra delle lor barbe con cipolle tagliate minute.

Take fennel in its season (…) I mean the white shoots that grow at the base of wild fennel; remove the outer layer and select the most tender parts. Wash them and form bundles as one would with broccoli, and place them in a pot with oil, water, and salt. Cook them thoroughly, and to thicken the broth, add breadcrumbs that have been soaked in broth and passed through a sieve. Season with pepper, cinnamon, and saffron. When cooked, serve them hot with their broth. If it is not a fasting day, cook them with crusts of Parmesan cheese and substitute butter for the oil. Alternatively, you can prepare a soup using the fennel fronds with finely chopped onions.

The use of spices—pepper, cinnamon, and saffron—in this recipe harks back to medieval culinary traditions.

During the Middle Ages, spices were treasured commodities, prized for enhancing food flavor and as markers of social status. Pepper, in particular, was so valuable that it was often referred to as "black gold."

However, by the 16th century, the increasing availability of spices due to expanded trade routes made them more accessible, though they retained their association with wealth and refinement.

For Renaissance diners, spices were not merely culinary tools but symbols of luxury and cosmopolitanism, connecting the dining table to the distant corners of the known world. In Michelangelo's time, dishes like a simple fennel soup infused with exotic spices' warm, robust notes would have been a sensory delight and a quiet assertion of one's place in the social hierarchy.

Foeniculum vulgare harvesting from a late 14th-century Tacuinum Sanitatis.

… and Wine

In Renaissance Italy, wine was a staple at every meal, valued for its taste and practical uses. Mixed with water, it disinfected unsafe drinking water—a practice inherited from ancient Rome.

Beyond its practical purposes, wine also played a key role in daily diet, especially for the lower classes. It was a source of essential calories and a complement to simple meals. The light, often diluted wines consumed by the lower classes differed significantly from the full-bodied vintages favored by the wealthy.

The wine was sometimes sweetened with honey or molasses or infused with herbs like fennel seeds to enhance flavor.

Wine also held cultural and symbolic significance, reflecting personal taste and social status. Michelangelo's shopping list shows his preference for vin tondo (full-bodied wine), reflecting a taste for quality wine. For the affluent, wine symbolized status, with tables featuring sweeter, aromatic wines or imported varieties like Malvasia prized for their exotic flavors.

Beyond its dietary role, wine held religious significance. In Christian liturgy, it was central to the Eucharist, symbolizing Christ's blood, which elevated its importance in society.

During the Renaissance, wine emerged as an object of study and appreciation, reflecting its growing cultural importance. This interest is illustrated by figures like Sante Lancerio, Pope Paul III's sommelier. In his writings, Lancerio meticulously documented the pope's preferred vintages, describing their characteristics and origins.

Later, in 1595, physician and wine historian Andrea Bacci explored wine's cultural and medicinal qualities in his De Naturali Vinorum Historia.

However, not all views on wine were favorable. Our old friend Giovanni Della Casa, in his Galateo (1558), cautioned against excessive drinking:

Né crederò io mai che la temperanza si debba apprendere da sì fatto maestro quale è il vino e l’ebrezza.

Nor will I ever believe that temperance can be learned from such a teacher as wine and drunkenness.

While not condemning wine, Della Casa emphasized moderation as essential for maintaining the dignity and composure required of the Renaissance man in social settings.

Guido Reni, Drinking Bacchus (1623) housed at Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Dresden).

Although Michelangelo's shopping list appears modest at first glance, it offers an unexpected view into the culture and customs of Renaissance Italy.

Tortelli, fennel soup, and wine—seemingly ordinary foods—carry meanings that transcend their role as food. They reflect the ingenuity of Renaissance kitchens, wine's social and spiritual role, and the evolving tastes that linked medieval traditions to modern culinary practices.

This simple document reminds us that even the most humble records can reveal profound insights into daily life, connecting the ordinary details of one man's table to the broader currents of history, culture, and identity.

Bibliography

Morgante: Depictions of a Renaissance Jester Turned Duke

La cucina rinascimentale tra banchetti e nuovi ingredienti

Bartolomeo Scappi, Opera Di M. Bartolomeo Scappi, Cvoco Secreto Di Papa Pio Qvinto, divisa in sei libri. (1570)

Gillian Riley, The Oxford Companion to Italian Food (2007).

Gillian Riley, Renaissance Recipes (1993)

Massimo Montanari, Il cibo come cultura (2004)

Missed the first episode of this article?

If you're interested in Renaissance Italy, you may enjoy these other posts on the topic.

This is great! While I'm an ardent believer in the "Torta e tortello gospel," I find the fennel soup recipe quite appetising. And I think they used to drink wine also because water wasn't to be trusted much back then, especially in the cities. And how funny is little Bacchus, relieving himself while drinking, with the wine barrel "relieving" itself too.