How Did Cleopatra Die? Poison, Power, and Myth

The uncertain science of a queen’s last act

(…) For though his messengers came on the run and found the guards as yet aware of nothing, when they opened the doors they found Cleopatra lying dead upon a golden couch, arrayed in royal state.

And of her two women, the one called Iras was dying at her feet, while Charmion, already tottering and heavy-handed, was trying to arrange the diadem which encircled the queen's brow. Then somebody said in anger: "A fine deed, this, Charmion!" "It is indeed most fine," she said, "and befitting the descendant of so many kings." Not a word more did she speak, but fell there by the side of the couch.

(From The Parallel Lives by Plutarch, Antony, 85)

This is how Plutarch described Cleopatra's end: lying on a golden couch, dressed as a queen, her attendants beside her until the last breath. The scene has traveled through centuries, unchanged.

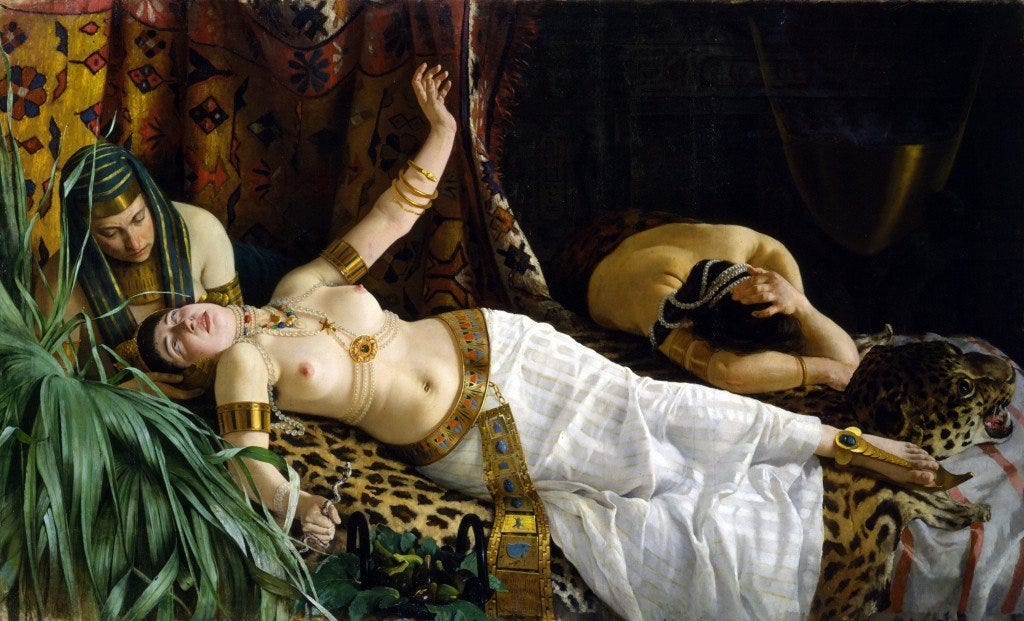

Achille Glisenti, “The Death of Cleopatra” (1878–79). Civic Museums of Brescia.

Behind the scene, remains the enigma: how did Cleopatra really die?

Plutarch, writing more than a century after Cleopatra’s death (30 BC), reported several versions. Some claimed she let herself be bitten by a serpent, perhaps smuggled in a basket of figs. Others spoke of a poison concealed in a hollow hairpin.

Plutarch himself had noted the queen's familiarity with toxic substances:

Moreover, Cleopatra was getting together collections of all sorts of deadly poisons, and she tested the painless working of each of them by giving them to prisoners under sentence of death. But when she saw that the speedy poisons enhanced the sharpness of death by the pain they caused, while the milder poisons were not quick, she made trial of venomous animals, watching with her own eyes as they were set upon another.

She did this daily, tried them almost all; and she found that the bite of the asp alone induced a sleepy torpor and sinking, where there was no spasm or groan, but a gentle perspiration on the face, while the perceptive faculties were easily relaxed and dimmed, and resisted all attempts to rouse and restore them, as is the case with those who are soundly asleep.

(From The Parallel Lives by Plutarch, Antony, 71)

Cleopatra possessed at least basic knowledge of medicine, and she is said to have prepared her own cosmetics.

She lived in Alexandria, a city that had been one of antiquity's premier medical centers since Hellenistic times. The local medical tradition had developed a strong expertise in pharmacology and toxicology: Galen even records that cobras were used there to grant a condemned prisoner a quick and merciful death.

So, in Cleopatra's circles the effects of various poisons would have been familiar territory.

The choice of poison carried a meaning beyond practicality. The cobra, associated with the pharaonic uraeus, was a regal emblem, and Cleopatra could have chosen this form of death for its resonance.

Modern scholars, however, have revisited these testimonies and generally consider the snake-bite theory the least likely. It would have posed too many practical problems: a serpent large enough to kill several people hidden in a basket, visible bite marks, and the long interval required before the poison took effect.

By contrast, a cardiotoxic or paralyzing substance could explain the rapid death and the absence of marks on the body, except for ‘two slight and indistinct punctures,’ as Plutarch reports. A poison concealed in a hairpin fits better with the details transmitted.

Some have gone further, suggesting a disguised assassination.

Octavian had the motive: to eliminate a political rival who might become a symbol of resistance. He also had the means: his court had physicians capable of preparing a lethal mixture that simulated a snake-bite.

A political murder presented as suicide would have avoided unrest in Egypt. After all, Octavian also had Caesarion, Cleopatra's son by Julius Caesar, executed for the same dynastic reasons.

But the assassination theory has gaps: some argue that Cleopatra, as a defeated enemy, could have been executed publicly without such elaborate staging.

Suetonius adds another detail: Augustus, finding Cleopatra dying and wishing to display her alive in his triumph, called for a snake-charmer to suck out the poison. He had no luck.

The anecdote tells us more about the myth than the reality, but it shows how closely the serpent’s image was tied to the queen.

Perhaps the serpent was involved, but the poison did not come from a bite.

Strabo and Galen had already suggested that Cleopatra might have used a toxic ointment, applied to a self-inflicted wound or to skin broken with her teeth. Galen imagined that she could have pierced her own flesh with a bite, then smeared it with snake venom.

A more intimate, almost ritual gesture:

She wounded her arm with a very large and deep bite. Then, having procured a vessel, she collected the animal’s venom in it and poured it over the wound; thus, as the poison spread, she was soon able to die with ease, escaping the vigilance of the guards.

(From Galen, De theriaca ad Pisonem, 237)

So many theories are possible. Plutarch concluded with an admission which, after all, still holds true: “the truth of the matter no one knows.”

And it is precisely this uncertainty that makes the scene unforgettable.

Cleopatra was not paraded in chains in Rome, as Octavian wished, nor did she die as any common enemy. On the golden couch, with the diadem adjusted by her last attendant, Cleopatra had already slipped beyond his reach.

That day, she lost a kingdom, but won immortality.

Bibliography

Plutarch, Parallel Lives, Vol. IX, Loeb Classical Library, 1920.

Galen, De theriaca ad Pisonem, 237 (translation is mine).

Retief, F.P. & Cilliers, L. “The death of Cleopatra.” Acta Theologica, Supplementum 7 (2005): 79–92.

Tsoucalas, G. & Sgantzos, M. “The Death of Cleopatra: Suicide by Snakebite or Poisoned by Her Enemies?”, in: Philip Wexler (ed.), History of Toxicology and Environmental Health. Elsevier, 2014.

Rosso, A.M. “Toxicology and snakes in Ptolemaic Egyptian dynasty: The suicide of Cleopatra.” Toxicology Reports 8 (2021): 676–695.