Along Route 144

Between snake charmers and tormented countesses, Roman armies on the march, and lakes that no longer exist

With Murray's "Hand-book for travellers in Southern Italy – being a guide for the continental portion of the Kingdom of the two Sicilies" (1855) in my pocket, I left Rome one Sunday morning for a short journey into a long past.

My destination was the Abruzzo region.

Murray wrote for English travelers who, in the mid-nineteenth century, came to Italy to rediscover the stages of the Grand Tour. Letters of introduction, mules, authorized taverns: that was a world where access to places required social intermediaries, multiple logistical difficulties, and extended timeframes.

Today, it takes just two hours by car from Rome, along a comfortable highway.

In 1855, these areas were still under Bourbon rule, as the very title of the guide reminds us: Italy, after centuries of foreign domination and political fragmentation, would unite only a few years later, in 1861.

Alba Fucens: the layers of time

The journey toward the archaeological area of Alba Fucens crosses countryside that Murray would not have recognized.

The site emerges from the hill like a repertoire of ordered ruins: the paved forum, the walls, the amphitheater carved into living rock. The early medieval church of San Pietro in Albe rests on the remains of a pagan temple dedicated to Apollo. Roman columns were integrated into the medieval naves without embarrassment.

From the hill where San Pietro stands, you can admire a spectacle so familiar in Italy: the layers of its millennial history succeeding one another, each leaving its mark as a legacy to the next.

Below, the archaeological area corresponding to the Roman colony of Alba Fucens, founded in the territory of the Italic population of the Aequi. Rome had spent decades subduing these mountain tribes: the Aequi controlled the Apennine passes and resisted until the 4th century BC, when a series of military campaigns definitively broke their autonomy.

Alba Fucens was founded in 303 BC as a Latin colony, serving as a strategic outpost to oversee the conquered territory and a bridgehead toward the territory of Marsica. Six thousand colonists received lands confiscated from the defeated Aequi. The position was not random: it dominated the Fucino plain and controlled access to the Via Valeria, the artery that would connect Rome to the Adriatic.

From the church's elevated position above the Roman site, you can make out the ruins of the medieval village and castle of Albe, ancient fief of the Orsini family.

An earthquake in January 1915 devastated this region, causing the abandonment of the medieval village and the collapse of the church of San Pietro. The church was later rebuilt in the 1950s, but walking along the path, you still step on its rubble. The remains of its decorations are now preserved in the Museum of Sacred Art in Celano.

The lake that is no more

What is now the Fucino plain was once a large lake (extending on average about 155 square kilometers), which was then definitively drained in 1878 by the Roman banker Prince Alessandro Torlonia.

Lac Fucino et les montagnes des Abruzze by Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld (1789, Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Murray extensively documents the various attempts to "tame" the lake and its devastating floods, dating back to Roman times. He recounts a curious incident that occurred during the reign of Emperor Claudius, who oversaw the first major drainage works on the Fucino, including a spectacular mock naval battle held before the emissary was opened:

The naumachia and gladiatorial games which took place in honour of the event, in the presence of Claudius and Agrippina, are described by Suetonius and Tacitus; but when the waters were let into the passage, they met with an obstruction which caused them to regurgitate with such impetuosity that the bridge of boats, on which the emperor and his court were assembled, was nearly destroyed.

Tacitus, after recording the heroic bravery of the malefactors who manned the fleet for this cruel display, describes the panic caused by this accident, and the accusations heaped by Agrippina upon Narcissus, the director of the works, who recriminated by an attack on her character and ambition.

It is believed that at a subsequent period Claudius completed this magnificent work, which Pliny ranks among his greatest undertakings.

Also in the Celano Museum are preserved the archaeological remains brought to light by the drainage work, which were later entered into the Torlonia collection.

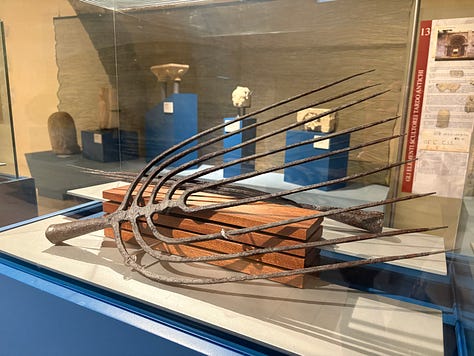

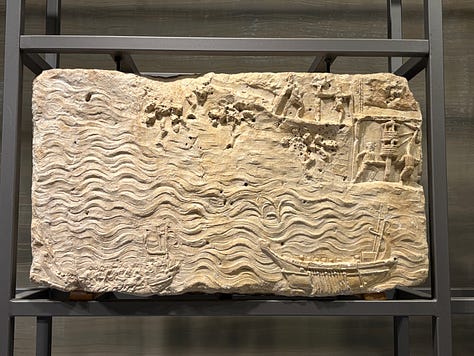

The fishing spears, for example, testify to the fishing activity that was practiced here. The most admired piece, however, is the second-century AD limestone relief with views of the lake and its territory.

Celano: Jacovella, a mother besieged

The castle of Celano, dating to the late 14th century, dominates the Fucino plain from above, a quadrangular mass with cylindrical towers that today houses a museum.

Murray recounts the story of the "misfortunes of the Countess Covella"

The Contado of Celano is noted in Italian history for the misfortunes of the Countess Covella, and for the cruel and unnatural warfare waged against her by her son Ruggierotto.

Covella was the last descendant of the Counts Ruggieri, of Norman extraction, who held a considerable tract of the neighbouring country. Her son, desirous of possessing himself of his mother’s lands, joined the Anjou party, and prevailed upon their captain, Piccinino, to support him in wresting the Contado from her.

After seizing Celano, they besieged the Castle of Gagliano, in which the Countess had shut herself up in the hope of holding out until she should receive aid from Ferdinand of Aragon. But, after a few days, the fortress was carried by storm. Piccinino seized the treasures on his own account, and consigned the strongholds of the Contado to Ruggierotto, who threw his mother into prison.

Napoleone Orsini, who, in the name of Ferdinand and Pius II., destroyed the remnants of the French party in the Abruzzi, defeated Ruggierotto, who set his mother at liberty to plead his cause with the Pope, who claimed the Contado himself. But Ferdinand, to avoid a quarrel, granted it, in 1463, to Antonio Piccolomini, Duca di Amalfi, the pope’s nephew and his own son-in-law, as a dower of his natural daughter, Mary of Aragon.

Jacovella da Celano (1418-1471) was the last heir of the Counts of the Marsi, descendants of Charlemagne. A genealogy that breaks in the 15th century through a sequence of forced marriages, early widowhoods, and a family siege.

Three marriages: the first, still a child, in 1424 to Odoardo Colonna, nephew of Pope Martin V, never consummated and later annulled. The second, in 1439, to Jacopo Caldora, who was almost seventy, and who died after three months. The third in 1440 to Lionello Accrocciamuro, from whom she had three children. When she became a widow for the third time in 1458, Jacovella found herself governing the county alone.

Her son Ruggero, barely of age, claimed his rights by force of arms. In 1462, aided by the condottiere Jacopo Piccinino, he besieged his mother in the castle of Gagliano Aterno. Three days of continuous attacks, then capture. Jacovella had to pay 120,000 ducats to regain her freedom. The fiefs passed to her son; she was left only with the county of Venafro, where she died before 1471.

The castle that today welcomes visitors with guided tours and captions witnessed a mother-son conflict, as documented in its archives.

Serpents and memory

In the same lands where Jacovella resisted family sieges, Murray observed a millennial cultural continuity:

These mountains abound with lynxes and wild boars; the banks of the lake with vipers, and the lake itself with water-snakes. The ancient Marsi, the inhabitants of this district, are celebrated by the Roman poets for their skill in charming serpents; and their descendants, even at this day, are found all over the kingdom earning a livelihood by the exhibition of their art (…)

In 1855, snake charmers were still practiced in rural areas of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. The descendants of the Marsi crossed villages with their baskets, perpetuating knowledge that Latin poets had celebrated two thousand years before.

The Via Valeria had brought Rome to Marsica, but had not erased everything. Certain knowledge was transmitted laterally, outside official channels. Imperial control assimilated, but left margins.

Today this tradition is probably extinct: it did not survive the lake, nor the countesses, nor the centuries that separate Murray from our era of highways and educational museums.

Tagliacozzo: a door worth knocking on

The last stretch of Route 144 winds toward Tagliacozzo, "the most important town of the district." Murray noted the possibility of a "hospitable palazzo" as an alternative to the poor conditions of the local inn:

The inn or tavern is wretched, but an introduction to the Mastroddi family will be sure to obtain admission into their hospitable palazzo on the piazza below the hill. Its fine staircase contains some marble fragments and Roman inscriptions.

It was a world where aristocratic hospitality mediated access to territories. He continues:

Mules or horses and a guide must be hired to proceed to Tivoli, about 30 m. distant. The path follows in great part the Via Valeria.

It is here that temporal distance closes. Murray’s Route 144, designed for English travelers with private carriages and social intermediaries, retraces the Romans’ Via Valeria, an axis of conquest and control. Today it is a state road: democratic, anonymous.

What changes is not the geography, but the way we move through it. Every road belongs to its time.

The invisible road

The Via Valeria still flows beneath contemporary asphalt, the fossil trace of an era when roads organized empires.

Murray traces its itinerary for the curious tourist who might have wanted to rediscover the ancient localities reflected in the modern ones:

The Via Valeria was opened by M. Valerius Maximus, about B.C. 260, from Tibur to Corfinium, and subsequently carried as far as Hadria. The stations on it were—

Tibur, Tivoli.

Carseoli, near Cavaliere.

Alba Fucentia, Albe.

Marrubium, S. Benedetto.

Cerfennia, near Coll’ Armele.

Statulæ, Goriano Sicoli.

Corfinium, S. Pelino.

Interpromium, Below S. Valentino.

Teate, Chieti.

Hadria, Atri.

Something of that past still lingers today: in place names, in the orientation of settlements, in the quiet persistence of certain memories that span centuries without explanation.

Not everything that remains is visible at first glance. But if you look closely, the traces are still there.

A charming way to discover hidden gems in Italy. Thanks, Historia Minuta!