Some time ago, I started collecting antique photographs—those small-format portraits popular from the mid-19th century, where people wear their Sunday best, pose, and wait (quite a while) to be immortalized by the pioneers of photographic art.

Last Sunday, I came across an image that likely dates back to the mid-1860s, judging by the clothing. This immediately made me think about another image I had seen at an exhibition I visited back in May.

It was the portrait Edgar Degas painted of his sister in 1863, now on display at the Musée d'Orsay.

The pose, expression, and dress are the same, a testament to how early photography borrowed stylistic conventions from traditional portrait painting.

Edgar Degas artist QS:P170,Q46373 Sailko, Edgar degas, thérèse de gas, 1863 ca, CC BY 3.0

Auguste Meylan, itinerant daguerreotypist

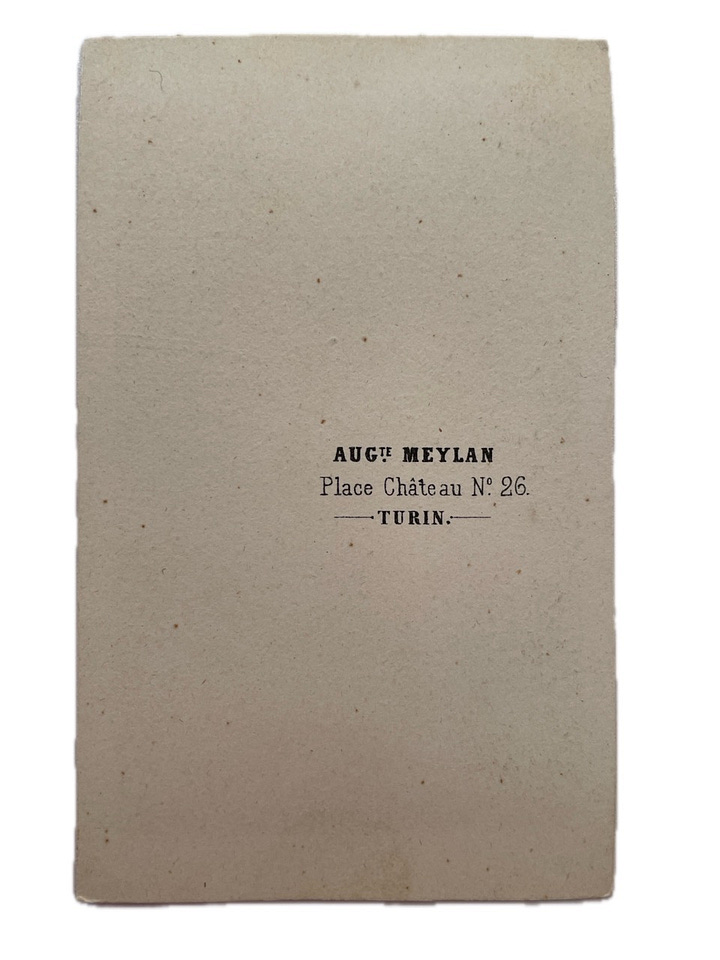

However, the story that intrigued me the most was written on the back of the photograph. The photographer's name is listed here: "Aug.te Meylan - Place Chateau N° 26 - Turin."

The first question, to which I have yet to find an answer, is: Why did Auguste shorten his name to Aug.te? After all, he only saved two letters!

The other question that piqued my curiosity is: Who was Auguste Meylan?

Thankfully, the internet came to my rescue, unveiling his fascinating story.

Auguste was Swiss, and by the mid-1840s, he was active in Geneva and later in Turin, in association with photographer Auguste Garcin. During their stay in Turin, Meylan and Garcin worked as portraitists in the studio of photographer Gioacchino Boglioni, boasting a new process from Paris (the daguerreotype was invented in Paris in 1839). An address is also listed: rue Charles-Albert 13. It's worth noting that Auguste's street was named after King Carlo Alberto, who ruled the Kingdom of Sardinia at the time, of which Turin was the capital.

In the years that followed, Auguste traveled between Switzerland and Italy: in 1849, he is documented as an itinerant daguerreotypist in Bern, and in 1850, he was back in Turin, where he received a bronze medal with Boglioni at the National Exhibition of Industrial Products.

In 1855, he moved his studio to 92 rue Rhône in Geneva, but by 1857, he had settled again in Turin.

In June 1851, an announcement appeared in the newspaper "Gazzetta di Parma" regarding an anonymous itinerant daguerreotypist—presumably Auguste—who, staying at the Albergo della Posta, offered “ritratti colorati in miniatura Dagherrotipa giusta il nuovo metodo di Parigi” (my translation: colored miniature daguerreotypes portraits according to the new Parisian method). Meylan returned to Parma again in 1852 and 1853. At the time (pre-Italian unification), Parma was the capital of another state: the Duchy of Parma, Piacenza, and Guastalla.

In 1857, he was back in Switzerland, at Le Sentier.

At the start of the 1860s, Auguste reappeared in Turin at Place Chateau No. 26. Here, he took the photograph of the elegant lady now in my possession.

Unfortunately, the information stops here: I don't know if Auguste ultimately settled in Turin for good or resumed his wandering, leaving no further trace.

I admit that reading about Auguste's endless travels has left my head spinning... but I believe it's a clear example of the excitement sparked by the invention of photography and the romantic figure of the "itinerant daguerreotypist."

The itinerant daguerreotypist was a key figure in the early days of photography, as they were photographers who traveled frequently to reach clients in areas without permanent photography studios. From Auguste's travels, we understand that his area of interest was Northern Italy, moving between the Kingdom of Sardinia and the Duchy of Parma, where he knew he could find an audience eager for his innovative services.

We should remember that the journey for an itinerant daguerreotypist was far from straightforward: they traveled with delicate, cumbersome equipment, including chemicals and silver-plated copper plates needed for daguerreotype creation. Thanks to pioneers like Auguste Meylan, photography spread rapidly across broad sections of the population starting in the mid-19th century.

This is the bourgeois

Back to the image in my possession, it is, more specifically, a carte de visite, a small-format, low-cost portrait made possible by the 1854 invention of another Parisian, André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri.

Collecting cartes de visite, especially those depicting celebrities, aristocrats, and European royalty, quickly became a craze. Additionally, the "democratic" nature of photography compared to painted portraits (especially after Disdéri's innovation) made it the self-representation medium of choice for the rising bourgeoisie. Through their portraits—traded and displayed—the bourgeoisie staged their respectability and economic success, creating a visual narrative of their social ascent.

The success of the carte de visite lies in how photography allowed people to construct their self-image. As Mary Warner Marien points out in Photography: A Cultural History:

The success of the carte-de-visite also derived from the liberal use of fancy furniture and painted backdrops calculated to make the sitter appear rich. Like the later daguerreotypes, cartes-de-visite encouraged sitters to construct an image of self-satisfaction and financial prosperity. Some photographers even stocked lavish clothing, which they rented to sitters for the photographic moment.

Thus, for the first time in history, technology allowed not only the privileged classes, but a wider range of people to construct and control their public image through photographs.

Isn't that the same thing we do today each time we post a picture on Instagram?Perhaps, the quest for self-image hasn’t changed as much as we think.

Sources

Mary Warner Marien, Photography: A Cultural History (2002)

Interesting and fascinating read.